Home » Posts tagged 'rural'

Tag Archives: rural

The Memory of Old Jack–evocative language

The Memory of Old Jack

by Wendell Berry

Author Wendell Berry is loved and even revered by many of his readers. This is the third book I have read by him with my book club. He has written a series of novels describing the land and the people of the fictional Port William community in rural Kentucky from shortly after the Civil War to 1952. As a part of this series, The Memory of Old Jack’s timeline is a little jarring as it jumps repeatedly between Jack on a special September day and the memories he dredges up from a lifetime of experiences. A hard working farmer, he soaked in wisdom about farming and about life from an older neighbor.

My opinion of the character Jack also bounced around as I read about the various events of his life; sometimes I found him admirable and at other times an enigma. He is a rough man, tied to the land he loves so much. He has some regrets about his choices in life, but doesn’t seem to be able to make different choices or fix past mistakes and still stay true to himself.

Perhaps it is because of my own creeping age or the recent deaths of many loved ones, but I found the book very sad. Another member of my book club called it “grim,” and I must agree. It is not sprinkled with uplifting light spots, nothing to raise the heavy veil. There are some supporting characters that I liked, but they did not make up for the melancholy of this tale. Wendell Berry is a good writer in the sense that he effectively writes what I will call poetic prose. A few chapters into The Memory of Old Jack, I was struggling to want to finish this book. I made an attitude changing decision to do a read/listen and that made all the difference. The written language took on a beauty when it became oral.

There is no plot per se; the book moves along from anecdote (in this case memories) to anecdote. Although Berry tells his tale through the main characters, I never found them likable. To like this book, the reader would need to find the characters engaging. For me, it was more a matter of waiting for the next shoe to drop as the story moves to its inevitable conclusion.

The Memory of Old Jack is a vehicle for Berry’s expression of his philosophies about preserving the land and the customs and knowledge necessary for self-sufficiency. Berry was a farmer for forty years in addition to expressing his ideas through environmental activism. A poet, novelist, and essayist, he also worked as a professor. His use of story to promote socio-political thought is reminiscent of the writings of Sinclair Lewis.

This dichotomy of beautiful language in a novel that plods along makes reviewing and ranking it difficult. It deserves five stars, top in my rating system, for eloquent, descriptive language. For elements such as plot and character, I can only award it three stars as a book that I would never read again and am unable to recommend.

Rating: 4/5

Category: Fiction, Historical Fiction, Literary Fiction

Notes: 1. #3 in the Port William Series but all can be read as standalones.

2. Some profanity

3. Narrator Paul Michael of the audio version produced by Christian Audio is good with women’s voices as well as men’s.

Publication: October 8, 1999—Counterpoint

Memorable Lines:

That is what Old Jack has always given him—not help that he did not need but always exactly the help he has needed.

His vision, with the the finality of some physical change, has turned inward. More and more now the world as it is seems to him an apparition or a cloud that drifts, opening and closing, upon the clear, remembered lights and colors of the world as it was. The world as it is serves mostly to remind him, to turn him back along passages sometimes too well known into that other dead, mourned, unchangeable world that still lives in his mind.

…it is hard to keep his mind, ranging around the way it does, from crossing the track of his hard times.Though he would a lot rather let them lie still and be gone, once his mind strikes into his old troubles there is no stopping it; he is in his story then, watching, as he has helplessly done many times before, to see how one spell of trouble and sorrow led to another.

The Wind in My Hair–compulsory hijab

The Wind in My Hair

by Masih Alinejad with Kambiz Foroohar

In her memoir The Wind in My Hair, Masih Alinejad, in exile first in Great Britain and later in America, tells the struggles she had and all Iranian women still endure with laws in Iran that make wearing the hijab compulsory from age seven. The “morality police” in that country take this law over what women wear to the extreme. Women can be beaten, flogged, and jailed if even a strand of hair escapes the hijab. Women who have resisted this compulsory law have had acid splashed in their faces and have been incarcerated, tortured, and sometimes raped.

Masih tells her personal story of an impoverished, but mostly happy, rural childhood with conservative parents. Always a bit of a rebel, Masih was expelled from high school in her final semester and jailed for belonging to a small anti-government secret society. Later as a parliament reporter, she was banned from the parliament building for asking the wrong questions.

In exile Masih worked tirelessly and sometimes under threats of violence for the rights of women in Iran. There are more issues involved than compulsory hijab, but that is a visible sign of the control men have over women in Iran. Masih used the tools of social media, especially Facebook and Twitter, to broadcast her positions in Iran where the government controls television and newspapers. The movements she started were given exposure internationally via the Internet.

Masih is highly critical of female politicians and government employees who visit Iran but are unwilling to bring up women’s rights in official discussions and wear some version of head covering during their visit. Masih made recordings of Iranian families’ stories about their dead or missing loved ones called The Victims of 88. Brave women flooded her social media accounts with pictures of themselves without the hijab in the interest of freedom. The Wind in My Hair is well-written by a journalist-storyteller who has lived the story she tells. It will grip you and not release you as you ponder the freedoms you currently enjoy in your own country.

Rating: 5/5

Category: History, Memoir

Notes: Perhaps because she was not raised American, perhaps because she is a journalist, Masih’s perception of current politics and reporting in the U.S. seem somewhat skewed. She clearly understands that you can’t trust reports in Iran, but does not seem to realize that there is censorship in the U.S. by big business, politicians, and the media working in concert. That viewpoint does not change the importance of her analysis of the Iranian government’s control over its people following the deposition of the Shah.

Publication: May 29, 2018—Little, Brown, & Co.

Memorable Lines:

“The Americans are coming to steal Iran away. They’ll kill us all.” I really thought we’d face another war immediately. It was not rational, but, like millions of Iranians, I had been brainwashed by the daily propaganda on the national television and radio stations. I thought it was only Khomeini who was strong enough to stand up to the greedy U.S. capitalists. Many years later, I discovered that Khomeini was a coldhearted dictator who ordered the execution of thousands of Iranians.

I didn’t even know what charges I faced. No one had read the complaint against me. I had no lawyer to defend me. I was forced into giving a confession, and now all that remained was for this judge to pass a sentence. It didn’t sound very just. Later in life, I discovered that there is not much justice in the Islamic Republic.

There is a predictable cycle in Iranian politics, as predictable as the weather. Every year, for a few months, the government relaxes its grip and some actions are tolerated—women can show a few inches of hair under their head scarves, or men and women can actually walk together without being married, or the newspapers can publish mildly critical articles. Then, just like the dark clouds that gather in late autumn, the freedoms are taken away and transgressors are punished.

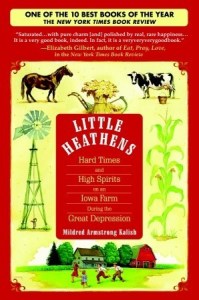

Little Heathens–Hard Times and High Spirits on an Iowa Farm During the Great Depression

Little Heathens

by Mildred Armstrong Kalish

There are a variety of tales and anecdotes about life during the Great Depression, yet many who survived don’t want to talk about it. The experiences of those in the cities were quite different from those living in the country. Regardless of location, however, all but the very wealthy suffered and their lives and perspectives were formed or altered by their experiences.

In Little Heathens, Mildred Armstrong Kalish shares what life was like for herself and her extended family. It is somewhat difficult to distinguish between the normal trials of endless farm work and the efforts needed to reuse and repurpose items because of deprivation of money and resources. “Thrown away” was a foreign concept during this time and thrift was the champion of the day. Kalish shares the many saving and “make-do” tricks that were common during the Depression and some that were uncommon. Many of those have fallen out of use, but are still handy to know and good examples of the resourcefulness of our predecessors.

Kalish lays her memories out forthrightly, not concealing or varnishing the stories. Many are humorous and several are gasp-worth. Children worked alongside adults learning by example and experience. Farm life required the whole family to pitch in. Chores were divided by age and gender, but not strictly. For example, Monday Wash Day was a very physical, all-day task for which preparations began on Sunday night. Children and adults wore the same set of clothes all week, and everyone participated in wash day. The need for everyone to work together is apparent in the book over and over again.

Kalish addresses the many aspects of life at that time as seen through the eyes of a child who was an active participant. She has an incredible memory for detail right down to how to catch, kill, and prepare a snapping turtle for consumption. She also discusses the social aspects of community inside and outside the family unit. Her life was unique in that she lived in town during the winter and on a farm during the growing season because of her family situation. Her life was very different in each place, but the expectations of a good work ethic and attitude never changed.

The author viewed the hardships of her childhood as instrumental in her many achievements later in life. From success as a “hired girl” to working her way through college to her happy marriage and career as a professor, Kalish gives credit to her family, especially her mother: “Mama’s ability to meet challenges head-on and with a positive attitude created in us kids a sense of confidence that there was a way to solve every problem—just find it.” Although her life was hard, it was not unhappy and she prizes the memories of her past. I enjoyed her writing style, learned from the information she shared, and relived some of my past as I have memories of my Depression-era parents handing down wise sayings and thrifty values. Well done, Mildred Armstrong Kalish!

Rating: 5/5

Category: Memoir

Publication: May 29, 2007—Random House (Bantam)

Memorable Lines:

Mama, Aunt Hazel, Uncle Ernest, Grandma, and Grandpa had a real gift for integrating us children into farm life. Working alongside us, they taught us how to perform the chores and execute the obligations that make a family and a farm work.

An Old Maid (that’s what we called unmarried women in those days) was asked why she didn’t try to find a husband. Her reply was, “I have a dog that growls, a chimney that smokes, a parrot that swears, and a cat that stays out all night. Why do I need a husband?”

After our chores and household duties were done we were given “permission” to read. In other words, our elders positioned reading as a privilege—a much sought-after prize, granted only to those goodhardworkers who earned it. How clever of them.

She kept all of her needles stuck into a red felt pincushion which she had owned since just before God.